THE WAR OF 1812

CAUSES FOR WAR

From the 1790s to the early 1800s, wars raged between France and the world. The fledgling United States, while trading supplies with both France and Great Britain, found itself in the middle of the conflict as the European countries vied for supremacy on the Atlantic. Numerous American citizens were pressed into services in the British Royal Navy and American merchant ships and cargo were seized by both sides. President Thomas Jefferson responded with the Embargo Act of 1807 and his successor James Madison continued with the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 to stop exports to those warring powers.

In the Old Northwest Territory, consisting of the state of Ohio and the territories of Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin, settlers were encroaching on American Indian lands. Although treaties between the US Government and American Indian tribes banned settlement and military occupation of tribal lands, these treaties were disregarded. From 1806 and 1811, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh sought to unite the Northwestern tribes against the American expansion into their lands. In 1811, William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, directed military attacks on the villages and camps of Tecumseh’s followers throughout the territory. Upon reaching Tecumseh’s village of Prophetstown, he reported a discovery of arms and supplies from British agents in Canada which he believed provided proof of British involvement in attacks on American settlements.

Citing free trade, sailors’ rights, and peace on the northwestern frontier, President James Madison signed an Act of Congress formally declaring war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812.

1812

The West

General Hull’s army finally reached Detroit on July 5, 1812. The British only had a small garrison at Fort Amherstburg and Hull decided to launch his invasion on July 12. The Americans landed at the town of Sandwich and sent detachments out to seize supplies and to scope out the British defenses. General Hull decided that he would not be able to take the fort without heavy artillery. When he heard that Fort Mackinac in the north had surrendered to a surprise attack, Hull retreated back to Detroit.

General Sir Isaac Brock, the British commander of Upper Canada, was able to rush up Lake Erie with reinforcements for Malden. After a short bombardment, General Brock threatened Hull with a vicious attack if he did not surrender. Cut off from supplies and reinforcements, Hull’s army laid down its arms on August 16, 1812.

The fall of Detroit meant that control of the Michigan Territory, from the straits of Mackinac all the way south to the Maumee River, reverted to the British. The loss of Hull’s army also mean that forts and settlements throughout the Northwest frontier were threatened.

The Americans on the Northwest frontier, especially in the states of Ohio, Kentucky and Pennsylvania were not idle after the fall of Detroit. Several thousand volunteers had already been raised to reinforce Hull’s army. William Henry Harrison, former governor of the Indiana Territory, was given command. He marched to Fort Wayne and sent out detachments to burn American Indian villages in retaliation for siding with the British.

The East

General Stephen Van Rensselaer decided to launch an attack across the Niagara River in October. On October 13, he ferried US regulars and New York militia to attack British outposts on Queenston Heights. The Americans succeeded in capturing the British positions, but several regiments of New York militia refused to cross over to reinforce them. General Isaac Brock rallied his troops and attempted to storm the heights, but was killed. His second in command, General Roger Sheaffe, surrounded the remaining Americans and forced them to surrender. This was the second major disaster of the war for the United States.

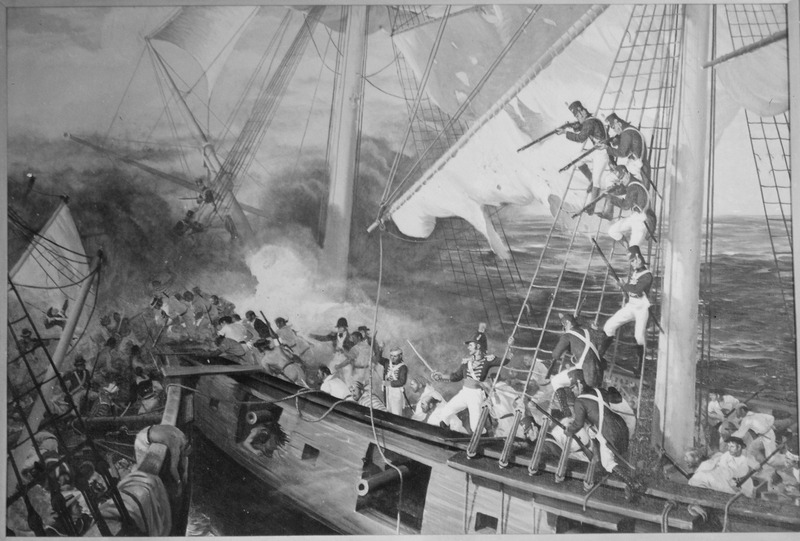

At Sea

In 1812 Great Britain had the largest navy in the world, numbering over 600 commissioned vessels and nearly 100 ships of the line. However, it was chronically short on manpower, and the fleet was worn out from two decades of blockading French ports. The British frigates of the time were smaller than 50-gun American ships like the Constitution, so while collectively they had a bigger force, the Royal Navy was weaker ship-to-ship than the US Navy

The Americans kicked off the war by setting their big frigates, including the USS Constitution, loose in the Atlantic to attack British shipping. In the first months of the war the defeats at Detroit and Queenston Heights were balanced by victories in ship to ship duels between USS Constitution and HMS Guerriere, the USS United States versus HMS Macedonian, and the United States versus HMS Java.

Congress also authorized private vessels to sail for the United States as privateers, and hundreds of small schooners and brigs were soon cruising the world’s oceans. Combined with French privateers, this soon took a drastic toll on British shipping and forced Great Britain to adopt a convoy system.

1813

The West

January 1813 found a large army of American soldiers advancing on Detroit in three columns. General James Winchester with Kentucky volunteers and US regulars had been at Fort Wayne since September, and slowly marched down the Maumee River towards the rapids. Generals Harrison and Joel Leftwich were advancing from Central Ohio with Virginia militia and regular infantry and artillery. A Pennsylvania brigade under General Richard Crooks and Ohio militia were marching from the east. Harrison was in overall command and wanted his forces to meet at the Maumee River.

Winchester and his men were far ahead of the other columns. When they reached the Maumee rapids, they met French-American citizens from Frenchtown (modern-day Monroe, Michigan) and were convinced to liberate the town from the British. A successful attack on January 18 turned bad a few days later when General Henry Procter led a surprise assault on the American camp on the morning of January 22.

In the wake of the battle, American prisoners of war and wounded soldiers were attacked by Procter’s American Indian allies. The violence led to outcry in the US and especially fury in Kentucky, where most of the victims hailed. The battle cry of the American army became “Remember the Raisin!”

General Harrison had lost one third of his army, and wet weather prevented the rest of his men from marching to Detroit. He settled down at the Maumee rapids and ordered Fort Meigs built to protect his supplies and artillery. Over the next few months, Harrison’s army dwindled to 700 men as militia enlistments ran out.

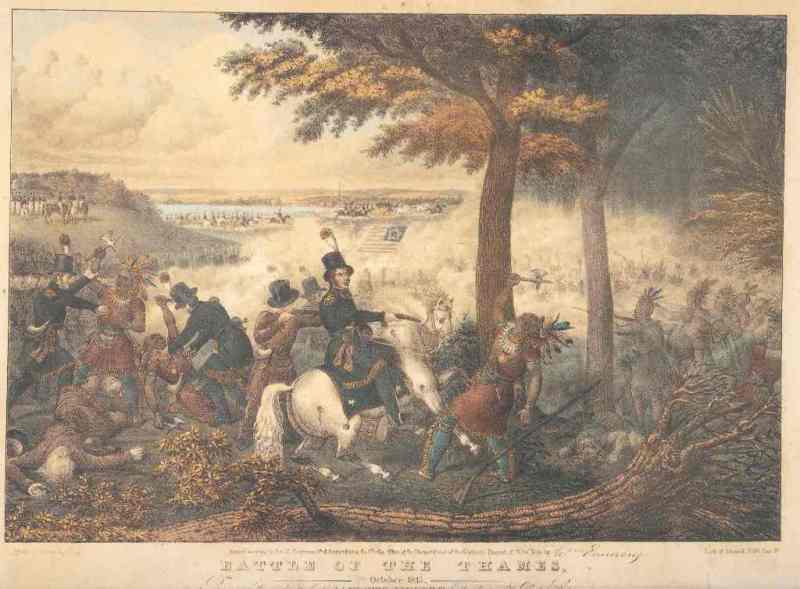

In the spring and summer of 1813, General Procter led several attempts to destroy Fort Meigs and other American forts in Ohio. In September, after Oliver Hazard Perry led the American Lake Erie squadron to victory at the Battle of Lake Erie (September 10), General Harrison was able to launch an invasion of Canada. He recaptured Detroit and Malden and caught up with General Procter at the Battle of the Thames on October 5. Procter fled and Tecumseh was killed, leading to the end of large scale warfare in the west.

The East

Americans took control of Lake Ontario and landed troops to capture York (modern Toronto) on April 27 and Fort George a month later. American troops looted and burned some public buildings in York. The British later retaliated by burning Buffalo, NY and Washington D.C.

Later in the year, two large American divisions converged on Montreal. In two separate battles, at the Battle of the Chateauguay on October 26 and the Battle of Crysler’s Farm on November 11, the American invasion was turned back.

The South

A new theater of war was opened with hostilities between American settlers in the Southeast and the Creek tribesmen known as the Red Sticks. These tribes had been in contact with Tecumseh before the war. Strife between factions led to a civil war within the Creek people. As the Americans got involved, militia General Andrew Jackson led forces from Tennessee and other southern states. The conflict intensified after the killing of 400 white settlers at Fort Mims on August 30, 1813.

At Sea

In June, Captain James Lawrence of the USS Chesapeake was challenged to a single ship duel by Captain Sir Philip Broke of the HMS Shannon. The Chesapeake was captured and Lawrence died from wounds, but his last words, “Don’t give up the ship!” were soon immortalized by his friend Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry.

1814

The third year of the war found American and British forces at a stalemate. The United States government was going deep into debt and many politicians doubted whether it could afford to pay for the war through several more years. Recruitment for the Regular Army was flagging, and Congress raised the bounty for recruits dramatically. For the first time, black soldiers served alongside whites in the US Infantry Regiments. There was also talk of systematically raising regiments of black soldiers.

In Europe the Napoleonic Wars had ended with the abdication of Napoleon, and Great Britain was able to shift many veteran regiments to fight in North America. Governor General Sir Prevost began planning a counter offensive against the Americans.

The North

Brigadier General Winfield Scott had spent much of the spring training his brigade in camp. In early July, his and two other brigades under the overall command of Major General Jacob Brown crossed over into Canada on the Niagara River and captured Fort Erie. The Americans met and defeated a British force at the Battle of Chippewa on July 5. They later met a reinforced British army at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane on July 25, leading to a bloody but inconclusive fight.

By August, General Brown had been cornered by the British at Fort Erie, where he successfully defended the fort against a British assault on August 13. After several successful American counter attacks the British retreated on September 21, 1814.

To the east, General Prevost assembled a force of 11,000 men, including veterans of the war in Spain, to descend Lake Champlain and threaten American posts in the Northeast. On September 11 his land forces fought an indecisive battle with American defenders at Plattsburgh New York. His naval force, however, was completely defeated by the American squadron led by Thomas Macdonough. Without naval support, Prevost refused to advance any further and retreated back into Canada.

The South

A British fleet, reinforced with a force of about 4,500 soldiers and Royal Marines, landed in the Chesapeake Bay region in August 1814. On August 24, these troops defeated a larger American force at the Battle of Bladensburg, Maryland. Led by General Robert Ross, the British marched into Washington, D.C. and set fire to the public buildings and navy yard there before returning to their ships. The White House was reduced to a charred shell.

On September 12, the same British force landed at North Point near Baltimore. They advanced inland, pushing back an American army at the Battle of North Point. General Ross was killed by an American rifleman, but his successor pushed on to the outskirts of Baltimore. The British fleet sailed into range of the Baltimore defenses (including Fort McHenry) on September 13. They failed to make a dent in the fortifications, and the British decided to withdraw instead of fighting their way into the city. The bombardment of Fort McHenry gave rise to Francis Scott Key’s famous poem of the same title, which in turn provides the words for the National Anthem of the United States.

1815

New Orleans

The American and British negotiators at Ghent in Belgium had settled on a peace settlement in December of 1814. Since no major territory had been gained or lost through the three years of war, the status of the United States and Canada was to return to what it had been before the war started. The Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 was signed on December 24, 1814.

Word took time to reach the American coast, and it wasn’t until January that the news of peace reached most armies in the field. Congress ratified the treaty in February, 1815. In the meantime, the British had sent a fleet and an army of over 8,000 men to capture New Orleans.

On January 8, the British advanced in force on the American earthworks outside New Orleans. The frontal attack was quickly repulsed by artillery, musket and rifle fire. The British commander, General Edward Packenham, and nearly 300 British soldiers were killed, as well as over 1,200 wounded. Only a handful of Americans were killed or wounded.

THE RESULTS OF THE WAR

After hostilities ceased, the forts and territory gained by either side were returned. Little had been accomplished towards the American goal of invading Canada. However, tribes of American Indians in the Northwest signed two treaties, in 1814 and 1817, which surrendered most of their lands to the United States. The War of 1812 spelled an end to warfare between Great Britain and the United States. Despite several rebellions and attempts by private groups, the United States would never again attempt an invasion of Canada.

"The fighting men of the Union are reckoned at a million. Not a twentieth part of that are needed to reduce Canada - and shall we not have it?"

~ Franklinton, Ohio Freeman's Chronicle

October 19, 1812

Image Credit: Fort Meigs